Are we living in a simulation? Do multiple versions of ourselves exist in parallel universes living out their lives in different timelines? Could this explain not only the Mandela Effect but provide us with a new understanding of time and space?

We’ll explore these questions with our guest, MIT computer scientist and best-selling author Rizwan Virk, as well as discuss his recent book, The Simulated Multiverse: An MIT Computer Scientist Explores Parallel Universes, The Simulation Hypothesis, Quantum Computing, and The Mandela Effect.

Rizwan (“Riz”) Virk is a successful entrepreneur, investor, best-selling author, video game industry pioneer, and indie film producer. Riz received a B.S. in Computer Science from MIT, and a M.S. in Management from Stanford's Graduate School of Business.

Riz is the founder of Play Labs at MIT, a startup accelerator held on campus at the MIT Game Lab. He also runs Bayview Labs and is a venture partner with two venture capital funds: Ridge Ventures, and Griffin Gaming Partners.

Riz has produced many indie films, including Thrive: What on Earth Will It Take, Sirius, Knights of Badassdom (starring Peter Dinklage and Summer Glau), The CW's The Outpost, as well as adaptations of the works of Philip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin.

Riz’s books include Startup Myths & Models, The Simulation Hypothesis, Zen Entrepreneurship, and Treasure Hunt: Follow Your Inner Clues to Find True Success.

Below is a partial transcript from our interview with Rizwan Virk—it has been edited for clarity and readability. For the full interview, click the YouTube link at the top of this page.

We started off by asking Riz why have the fields of science and academia taken a serious interest in the simulation theory in recent times? He tells us:

“When The Matrix came out over 20 years ago in 1999, this idea was really considered very much the realm of science fiction. It wasn’t something that was discussed in polite academic company, except for those who studied science fiction. A lot has changed in the past 20 years.

Probably the biggest thing that’s changed is that our computer processing as gotten much better. We all have these strong GPUs on our computers, and video games have really taken off from being a niche thing, to being something that everybody is exposed to on a regular basis.

Another is that computer science has gotten to be more respected across different fields. If you go back 50 years, computer science was separate from other fields and was viewed as a kind of applied mathematics. But today, you can’t really work in any fields without really understanding how computers can help you—not just in terms of running programs, but more importantly, how the other sciences might have an underlying layer of information.

There was a famous physicist at Princeton who worked with Einstein and with many of the other pioneers of quantum mechanics in the last century named John Wheeler. He coined the phrase, “it from bit”—he reached the conclusion that anything that is a physical object (like this table that I’m near or this chair that I’m sitting on), consist of bits of information, and that the only thing that distinguishes one particle from another particle are the values of these bits; so he realized there was no such thing as a particle.

So I think computer science and information theory in particular, have impacted all of these areas. That’s part of the reason why so many people are interested in this, and are coming at it from a technological or scientific point-of-view.”

Riz has written two books on this topic—the first book titled, The Simulation Hypothesis and his most recent book, The Simulated Multiverse. He tells us what interested him about this subject, and why he considers that we’re living in a simulation (much like a video game) a real possibility:

“I’ve always been interested in the topic going back to when I was a kid and I would watch episodes of Star Trek with The Holodeck in there, which is a way that they could simulate reality. So I had always been interested from the point of view of science fiction

I spent the last decade in Silicon Valley in the video game industry. During that time, I visited a company in 2016 that was making a virtual reality game using a VR headset (they were still relatively new). I played a virtual ping-pong game and I had the headset on, I had the controller in my hand, and playing the game felt so realistic that, for a moment, I forgot that I was inside a VR headset in the office of a tech company.

I thought I was really playing table tennis against some opponent. Of course, there was no opponent, and there was no table. But that didn’t stop me from trying to put the paddle down on the table at the end of the game (just like I might do in a real game), and the controller fell on the floor. I tried to lean the on table, and I almost fell over.

That’s when I realized that our video game technology is getting good enough—such that at some point those video games will be indistinguishable from physical reality. I asked myself, what would it take to get there?

That really led to the genesis of my first book, The Simulation Hypothesis. I came up with a set of 10 stages of technological development that we would have to go through as a civilization, to get to that point (which I call ‘the simulation point’), where we can build something like The Matrix, which is fully immersive.

I started researching the simulation theory (which was still fringe, but more respected in the academic community as a field of study), and the more I looked into it, the more I realized that we could get there—and if we could get there, is it possible that other civilizations have gotten there?”

We asked Riz about what do traditional Eastern and Western religions have to say that would support the idea that we are living in some type of simulation (which he covers in his book, The Simulated Multiverse). He said:

“When you look at the bigger religions, you have the Judo-Christian line of religions and you have the Eastern religions of Hinduism and Buddhism. They’ve all been telling us that the physical world around us is not the real world. Hinduism and Buddhism explicitly say that the world around us is Maya—which is an old Sanskrit word which means ‘a carefully crafted illusion.’

In fact, within the Buddhist traditions they use a very strong metaphor of dreaming—Buddha means literally ‘to awaken,’ as in, to awaken from a dream. We’ve all had that experience when we’re inside a dream and we think it’s real, but then we wake up and realize that it wasn’t so real. So the Eastern traditions have been telling us this all along.

There’s also this idea of the Lila, or ‘the grand play,’ which is another term in the Hindu Vedas going back 5,000 years, which talks about what we think of as reality is like a stage play. That’s the same metaphor that Shakespeare used many centuries later when he said ‘all the worlds a stage and the men and women are merely players.’ We have to think of these as metaphors because they were written down thousands of years ago.

Some of these religions also say that we go in as a character, we come out, and we go back in as another avatar. Avatar is derived from the Hindu term which means ‘to descend’—and that’s what we do when we take on the digital identity within a video game. Some of these religions have also been telling us that everything is being recorded.

In the Western traditions, if we look at Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in particular, they have this idea of the Book of Life. The Book of Life (depending of who you talk to), is either just a list of people’s name who would get into heaven or, if you delve into a little more, its actually a series of deeds—the things that you have done in your life.

The Scroll of Deeds in the Islamic traditions and The Book of Life in Christianity and Judaism, are both metaphors for something that perseveres what has happened. In islam they’re actually very specific about this—in Islamic tradition, there’s two angels writing down everything you do. In the West they’re called recording angels because they record what you’ve done.

So if you were to build something like that, you can’t take that literally. It doesn’t make sense to have 14 billion angels sitting around just writing stuff. That metaphor of a book is something that could be understood back at the time when these religions were formed, but we have to think in terms of a broader reality.

I think if any of those religions were created today they wouldn’t use the metaphor of a book or the stage play. They would use a 21st century metaphor, which is that we are in an interactive stage play/dream where we can all make choices and all of those things are being recorded—and what does that sound like? An interactive, massively multiplayer, online video game.”

In 1977, during a speech at a science fiction in Metz, France, science fiction writer Philip K. Dick said:

“We are living in a computer-programmed reality ... that in some past time-point, a variable was changed — re-programmed as it were — and that because of this, an alternative world branched off.”

Philip K. Dick in early 1960's.

We asked Riz about Philip K Dick and his idea that we are possibly living in a “computer programmed reality” which Riz explored in both of his books. He tells us:

“Philip K. Dick was a visionary in many ways—he’s the author of the books that led to movies like Blade Runner, Total Recall, and the recent, very successful Amazon series The Man in the High Castle, which is about an alternate timeline where the Germans and Japanese won World War II and what would that be like.

I came across his work while I was researching my first book, The Simulation Hypothesis because he was one of the first to really say that we were living in this computer programmed reality. You can find video clips from his talk [given in 1977] online, and you can see the audience thinking, ‘this guy is just nuts, what is he talking about?’

I interviewed his wife Tessa B. Dick when I was researching the first book, and that quote has become quite famous. When I interviewed his wife (who’s written a couple of good books about Philip K. Dick), she said he actually came to believe that we were living in multiple timelines, and that The Man in the High Castle in particular was a real timeline where the Germans and the Japanese actually won World War II. But that there was someone outside of the timeline who rewound that timeline, and re-ran it again.

When I was working on my current book, The Simulated Multiverse, I went back to his talk and I listened to the whole thing and I read the transcripts—turns out that line was ad-libbed. It wasn’t in the original transcript that we are living in a computer programmed reality. But turns out what he was really taking about was not just that. It was about this changing of variables.

He said that the only clue we have is when some variable is altered—some change in our reality occurs. We would have the sense that we were reliving the same event. Saying the same things. We would have feelings of Déjà vu. He said that these feelings of Déjà vu are a clue that at some point in the past, some variable was changed and a new alternate timeline (or alternate reality as he called it) was branched off.

So I found this really fascinating and in-fact part of the reason why I wrote this new book, The Simulated Multiverse was because he was talking about not just a multiverse, but one where somebody can change variables and re-run it—and that is exactly what we do when we run a simulation.

If we were running a simulation of the weather, or a simulation of long-term climate, or a fruit fly population—we would run those things and we would change the variables and we would run them again. Why do we do that? We do it to get the more likely outcome, or the most optimal outcome.

Another thing that he said was that we would just need to find a group of people like him (because he said he remembered this alternate timeline), so we would need to find a group of people who remembered a previous-present, meaning a version of the present that had a different history than what he called the consensus gentium reality (which is what the majority remembers). As it turns out, now we have people online that remember things differently which is the Mandela effect.

So I found that he was talking about this idea way back when, but It really makes sense when you pair it with our current video game technology and our ability to run multiple simulations. That’s actually led me very much to writing this book, The Simulated Multiverse.”

For those not familiar with the Mandela Effect, Riz explains it as follows:

“The Mandela effect came about because there was a group of people who remembered Nelson Mandela having died in prison in the 1980s but, of course, in our reality he didn’t died in prison. He was released in 1990, became the first black president of South Africa and died in 2013.

It turns out there is a whole bunch of these types of effects where a subset of people remembered events happening differently, and these range from small things like is there something called Jiffy peanut butter or is it just Jif peanut butter to, for example, certain evangelical Christians who followed the Reverend Billy Graham, who swear he died many years earlier and that they watched his funeral on TV with very specific memories—just like people with every specific memories of Nelson Mandela and his wife speaking at his funeral way back in the 80s. So this effect was fascinating.

When I began to research it, I found that this effect wasn’t just isolated—it wasn’t just a bunch of people misremembering small things. It was pretty broadly based, and that most scientist had dismissed it.

When I looked into it seemed like the best explanation is this multiverse idea, and a simulated multiverse in particular. This took me right back to what Philip K. Dick was really talking about—which wasn’t just that we lived in a computer generated reality, but it was that variables could be changed and that would lead to slightly different timelines. In some cases, very different timelines, and that these timelines could be stop, rewound, and re-run.”

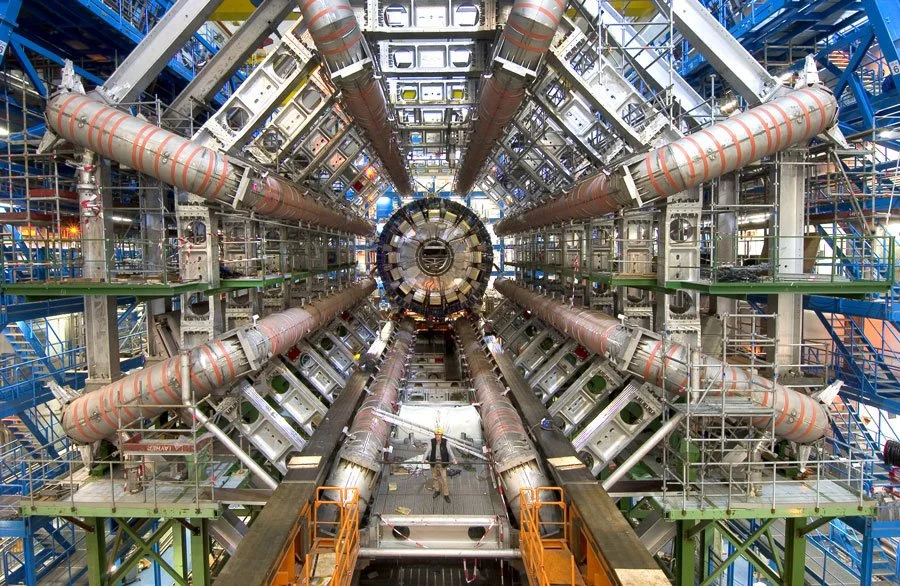

People have wondered in recent times if what CERN is doing with the Large Hadron Collider may have affected the timeline we are living in now. We asked Riz if, based on his research, CERN has that capability. He answered:

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Photo Courtesy of Maximilien Brice, CERN.

“I have looked into that as one of the possible causes of the Mandela Effect. Some people have theorized that CERN (when they were doing an experiment), either ended up branching off an alternate world, or connected with an alternate timeline, and that that’s when things went off-the-rails, if you will.

It kind of reminds me of that TV show called Counterpart—there they had a version of Berlin and they basically branched off another timeline, another universe. Then there was a duplicate version of each person.

I looked into it and I didn’t find that they have that capability in a knowing or witting way, so it’s possible in some unwitting way, that they were able to do this. The conclusion that I came to is that this branching of timelines is not that unusual—that it may be happening all the time anyway. So it’s very possible that this particular set of experiments, when they smashed together different particles, ended up changing the values of certain particles and that that resulted in a different timeline.

So, even though that may have accelerated some things—when you look at the Mandela effect, it’s not just something that took place in 2012. These things go way back, and there are lots of different Mandela Effects. It’s much more explainable if there are multiple timelines, not just two timelines or with a single branch.”

You can order your copy of Rizwan Virk’s, The Simulated Multiverse: An MIT Computer Scientist Explores Parallel Universes, The Simulation Hypothesis, Quantum Computing, and The Mandela Effect on Amazon. To learn more about Riz visit his website, and to keep up-to-date with his up-coming projects, be sure to follow him on Facebook and Twitter.